by Kyle Lauderman

Baileystown never grieved harder than the day Sam Morris let that out-of-towner Ally into his life. Sam Morris was one of us. His grandaddy built Baileystown from the ground up, taking on the inhospitable Nevada terrain and forging this land into the fine, humble town he knew it could be.

When Sam’s grandaddy established Baileystown in 1918, it wasn’t much, but it was the people’s. Dust roads and long lines of wooden structures made up most of downtown. Porches faced inward toward the road, perfect for sitting out in the sun and keeping this town a community. He raised his son – Sam’s daddy – here. In turn, Sam’s daddy left his own legacy on this town. He served as Baileystown’s mayor and, in 1942, led the initiative to get those dust roads paved. He was proud to raise his son Sam here.

From early on, everyone knew Sam would live up to the Morris legacy. He inherited his father’s heart and his mother’s warm smile. He was always such a kind-hearted boy with a special knack for remembering everything about everyone. Everyone remembered Sam as a young boy, befriending that shy Henry Anderson, son of the widowed Philip Anderson. They had been inseparable. Growing up, once other boys their age started experimenting with beers and girls, Sam and Henry spent their days helping out around town, usually aiding the elderly Leslie Carlton down at the local library.

Shortly after the two finished high school, Henry skipped town. He left the small, intimate setting of a close-knit community for the anonymity of some big city. That was more than twenty years ago. Sam, on the other hand, stayed in Baileystown, knowing it as his home, his destiny. He took up a full-time job working at the town bank and volunteered with the fire department on the weekends.

That spring before the summer that free-wandering Ally arrived, mayoral elections rolled around, and Sam decided, for the first time, to run. His name became the only one on the ballot. No townsperson could stomach the thought of letting their name be written next to “Sam Morris” and let their nature be compared to his. No one even bothered to count the vote.

“G’mornin, g’mornin, g’mornin,” he whistled on his walk downtown to his new office.

Sam became mayor, and the world made sense.

One May afternoon, Heather Reed marched up to Sam’s office, hollering about someone digging on her property. Sam intervened, solved it immediately and had it chalked up to one big misunderstanding. The smooth-talker he was, Sam could keep the peace between anyone. Hell, Sam could convince the Devil himself he was in the wrong.

With the fine gentleman Sam was, people in town started wondering when he’d get to matchmaking and establishing the next generation of the Morris namesake. His disinterest in spending time with women, having started as a maintenance of his youthful innocence, now proved to be a hindrance at this stage of life. Gussie Parsons suggested he “might not be the marriage type,” but Alan Stewart made sure to shut her down real quick. Sam Morris was a sensible man, surely one who learned from his parents to wait for the right woman.

Then, that woman Ally arrived.

The whole town shifted the day Ally arrived on that bus. Its door creaked open, and out came a girl looking ready for some “free love” movement–but about twenty years too late. Her cherry red shades served little function, powerless in the glare of the Nevada sun. The hems of her sundress–a sunset orange color adorned with stitchings of green carnations–barely made it halfway down her thighs. Little Katie Renee’s mother gasped in horror at Ally’s hair, long and blonde like Little Katie Renee’s, yet mangled with little green beads held captive in all the frizz.

“Yes, Ma, I know Jesus says that’s wrong,” Little Katie Renee swore, though she couldn’t remember which Sunday School lesson mentioned “hippie hair.”

Alan Stewart swore he could feel the ground tremor as Ally’s feet–bare as they were the day she was born–first made contact with the sizzling hot pavement. Ally stepped right off that bus like she belonged here, pulling her melon-sized sac of knick-knacks over her shoulder, and headed straight for Momma Leah’s diner across from the bus stop.

The bell above the diner’s front door rang in warning of Ally’s entrance. She sat herself down at the first empty stool at the counter, cross-legged with her feet swinging under the counter. She picked up a menu and started reading. From a few stools down, Sam Morris noticed her, looked her up and down. Then, like the polite, welcoming mayor he was, Sam moved to the stool next to her, introduced himself, and welcomed her to Baileystown. The two started talking. Anne Wyatt overheard Ally rambling on about her daddy–now dead–visiting Nevada once in hopes of seeing some UFOs sparkling in the night sky. And then Sam laughed, laughed like no one had heard him laugh before, not like someone talking to a stranger but like he’d been reunited with an old friend. That was the first sign of the end.

Some said God’s weeping over the affair ended Nevada’s six-month long drought. Ally rented a room at Ms. Caldwell’s Bed and Breakfast. That first week in town, she visited Sam’s office every single day at lunchtime. Then, that one fateful day, as Sam stood with Ally under the covering above the wooden porch of the mayor’s office, the clouds split open, and the downpour started. Heavy spouts of rain created a haze that fogged over the whole town. Within an instant, buildings across the street became distant shadows. The pattering of the droplets onto the ground echoed, making white noise that washed away any chance of outdoor conversation.

Ally held out her hand past the covering, let the raindrops beat against her palm. She closed her eyes and smiled. Sam laughed.

Like a child, Ally ran out into the rain. She just stood there, eyes closed, arms outstretched. The rain drenched her hair, flattening it to her head. Sam stood on the porch and watched in awe of the woman so unbothered by the cold stings of the rain on her skin. Then, he joined in. Sam Morris, a boy who grew up dry cleaning his clothes, ran into the rain like a wild animal. The rain soaked his clothes, ruined them, but Sam didn’t seem to care. The two just lingered there, two adults without any sense of social manners.

The next morning, Sam–hunched over and sniffling–visited Dr. Thompson’s office. Poor Sam’s face had less color to it than the fine layer of Nevada dust sprinkled on the road. Standing in the rain had invited sickness. Even though it was just a cold, Ally’s carelessness had taken a physical toll on him. She was trouble.

Three months in, Ally opened a flower shop downtown. Her dead daddy must’ve left her some money, but not much. Her flower shop was more of a wooden shack than a store, having bought the old tool shed outside Ol’ Parker’s bar that his wife sold flowers out of before she passed. Ol’ Parker wouldn’t share how much Ally gave him for it, but Heather Reed joked that, if we were lucky, the wind might blow her little shack over. Vines of ivy clung to the shack’s walls, crept up the sides, and wrapped around the wooden board above the front door that read “HER’S” in crooked letters painted on in black–not that it needed a sign. It amazed everyone that Sam Morris, a man who grew up with Baileystown’s library as his second home, would continue to see the woman who spelled “HER’S.” Of course, even if she could spell it right, everyone in town still knew who owned that shop, and all of a sudden, no one in Baileystown needed to buy flowers ever again.

You see, Ally herself was a flower. She was a sight, a spectacle, a natural beauty. She looked alright from afar. But up close, you’d see the thorns, smell the poison, feel the itch. The townspeople decided that–with Ally–if no one watered this plant, it might wither up and blow out of town.

It didn’t.

She spent her days loitering in that little flower shop, filled with plants but void of people. Whatever money her daddy left her, she poured into that shop, buying more and more fresh flowers to replace the old, dying ones no one had bought. Then, every workday around noon, Sam visited her with lunch from Momma Leah’s diner and bought flowers for his office on his way out. He bought so many flowers. He was her only customer. The town’s boycott meant nothing; the damage was already done. Ally had captivated Sam, corrupted him.

The two stuck like magnets. They walked through town together, one in tan suits and the other barefoot in pastel sundresses. Jim Nash said he sometimes spotted them spending the warmer nights up on the roof of the mayor’s office, just lying there, listening to the chirping of the night critters, studying every glow and twinkle of the stars above. Ally even stopped renting her room at Ms. Caldwell’s Bed and Breakfast, choosing to take up residence on Sam’s couch. At first, people tried to chalk it all up to Sam just being polite. Even her staying at his ranch house wasn’t too unusual. Sam Morris had always opened his heart and home to people. Last summer, when that one bachelor around Sam’s age passed through town, he had slept on Sam’s couch. That’s just the type of good man Sam was, the same type to let himself fall into Ally’s warped reality.

Deep down, no one could deny the changes. Just looking at Sam, anyone could see Ally’s influence was undeniable. He started to grow his hair a bit longer, letting the dark hair he inherited from his daddy shag down past his collar. Sam even unbuttoned his dress shirts three buttons lower under his suit jackets. Ally transformed him into a man Baileystown barely recognized. Heather Reed warned that Ally would be the death of him. Sam seemed skinnier and more tired than he used to. No doubt those late nights outdoors with Ally started to get to him. Someone needed to do something.

No one knows who did do something, but Alan Stewart saw it happen. Alan said he sat in the rocking chair outside Momma Leah’s diner, just watching the sun rise in the distance, when he saw Ally marching on up to her flower shop. As she walked up onto its wooden porch, Alan heard her yelp like a wounded animal. She fell back onto the road, trying to dig her fingernails into the tar as she wailed in pain. She crawled her way down to Dr. Thompson’s office. Jim Nash heard it took the old doctor more than two hours to pick out all the wooden splinters that sliced right into her exposed soles like tiny little knives. It seemed like someone had shaved the wood to be more rugged.

No one in town fessed up, but no one blamed the perpetrator. After that, Ally disappeared for a bit. Everyone believed she was spending her days recovering at Sam’s ranch house, but the town just enjoyed the relief of her being out of sight, out of mind. Over the next few weeks, the vines decorating the outside walls shriveled and died.

With Ally unable to walk, Sam gained some freedom from her grasp. He started spending nights downtown at Ol’ Parker’s bar. That’s where he was that night when the rusty bell above the bar door rang, and in came Henry Anderson, the childhood friend he hadn’t seen since their high school graduation in the sixties, two decades prior. Sam sat on the barstool in disbelief, couldn’t move a muscle if he wanted to. Henry laughed at Sam’s endearing shock. The sound of Henry’s laugh must’ve awakened Sam as he immediately shot up from his seat. He launched himself at his friend, wrapping his arms around Henry and nearly knocking him over in the process. Anne Wyatt swore she saw Sam’s eyes start to water.

Henry was an angel, a saving grace, the friend Sam needed to rescue him from Ally. Henry sure did look like an angel now too, ocean blue eyes that never seemed to not be gleaming with joy, a never-ceasing smile, and shaggy golden hair–wavy, not unlike Ally’s. While Ally’s injury stopped her from walking around town, Sam had room to breathe, daytime to spend in town with Henry and maybe remember the sensible Baileystown native he was at heart. Henry, with Sam’s help as mayor, even remodeled the rundown library the two used to volunteer at in their younger years. Baileystown celebrated the world being back on track.

Then, well.

Jim Nash saw it happen, said he caught only a glance before his better angels averted his eyes. One night, in the shadow of the back alley beside Parker’s bar, he saw two figures pushed against the wall, drunkenly sloshing around each other’s mouths, going at it like two baby birds fighting over a worm. Jim Nash said he’d never seen so much passion, so much sin. The two figures broke oral contact. The figure facing away from Jim Nash started to kiss along the neck of the figure against the wall. The figure pressed against the wall lifted his head up, looking up to the stars. At that moment, Jim Nash recognized him as none other than Sam Morris. Sam was unmistakable, as the moon shone on the strong Roman nose he inherited from his daddy. Sam’s fingers were tangled in the other figure’s golden curls, a shorter shaggy mess. Jim Nash said he’d recognize Ally’s wild nest of hair anywhere, assuming she must’ve tried cutting it during her recovery.

When Ally showed up the next morning to her flower shop, hair still long and tamed, the accuracy of Jim Nash’s tale started to be questioned. Everyone always knew Jim Nash to stretch some details in his stories, but never knew him as a liar. But anyone in Baileystown would’ve been ready to call him a liar if it meant what he saw wasn’t true.

As news and debate traveled, word must’ve eventually reached Sam because, standing at a podium in his finest suit in front of the whole town, Sam announced his love for and engagement to Ally. No one clapped. No one spoke up–the silence did all the talking. Even Ally just sat cross-legged in a chair to his side, staring at the ground. She couldn’t even look the town in the eyes.

A rushed wedding took place a few weeks later in the backyard of Sam’s ranch house. Everyone tried their best to attend, wanting to watch Sam regain his senses and call it off. No one had really been to Sam’s ranch house since Ally had taken up residence there, and people couldn’t help but be amazed that the backyard, once just a patch of dust and dirt, looked like an oasis in the Nevada desert. A picket fence outlined the property, interwoven by the same vines of ivy that identified that wooden shack downtown as Ally’s flower shop. Vibrant flowers and plants of all shapes, sizes, and colors sprouted out from the dull dirt. Collected pebbles of all shapes and sizes banded together to form walkways. Ally had turned the backyard into her own Hanging Gardens of Babylon.

Up until the very moment the ceremony began, townspeople kept squeezing in, making sure to sit on the left side of the garden–the side Sam stood on. People kept coming, chairs kept filling. Some started moving chairs from the right side into awkward positions in between rows on the left, others tried to share chairs, sit on laps, sit on the ground, stand–anything they could to avoid sitting on the right side of that garden.

Wedding starting, Ally stood up there in front of most of the town in a skimpy white sundress. Roses budded out from her hair, stems threaded into a long braid. Even Ally’s harshest skeptics had to admit her stance as a real beauty amidst the garden; she seemed more comfortable, more at home in her garden. But then again, it wasn’t hard to look the best at this wedding. Sam, pale and sweat dripping down his forehead, looked nervous, regretful. Henry–Sam’s best man–leaned against one structure or another the entire night. Anne Wyatt thought Henry might’ve been drunk, but Gussie Parsons disagreed. Gussie commented on Henry’s appearance–the prevalence of his collarbone through the open-chest floral shirt he wore, the lack of any meat on that boy’s bones. She thought he might be ill, that maybe Ally’s spell on his best friend had started to affect his health. The burgundy splotches that circled Henry’s eyes almost matched the vibrancy of the roses in Ally’s hair.

Sam and Ally didn’t kiss. When Father Robbins sealed their union, the two just closed their eyes and leaned their heads forward. They nuzzled their foreheads together and stayed there, just breathing slow, long breaths.

Not long after the wedding, Henry vanished. He must’ve smelt trouble or been chased out of town by Ally or something, but no one saw him after that night. But then again, no one saw much of any of them after the wedding. Ally locked Sam away in that ranch house, abandoning the town and its people. Sam Morris became mayor in name only.

A few months after the wedding, Alan Stewart claimed to have seen Sam Morris walking around Ally’s gardens in that ranch house backyard. Alan said he barely recognized him. Sam lost all his weight, appearing like a ghastly skeleton wandering amidst the greenery. Alan walked up to the garden fence and tried getting Sam’s attention. He startled Sam, who in turn swore he never knew an “Alan Stewart.” He started to yell, screaming for Alan to leave his property. Ally rushed out into the garden, grabbed Sam by the arm, and pulled him back inside the ranch house.

Every now and then, someone would suggest an emergency city council meeting, just to draw the absent mayor out of his home. No one followed through, out of fear of seeing the shell Ally created of the once great Sam Morris.

Within the year, news spread of Sam’s death. The townspeople found out from the local newspaper, the only effort Ally made to spread word. She never announced a funeral, just put out a notice in the paper that read:

SAMUEL MORRIS, BAILEYSTOWN MAYOR, DIED JULY 14, 1987.

No one could believe it. Heather Reed’s niece worked downtown for the lawyer handling Sam’s will. She told everyone how Sam left Ally the money, the ranch house, and–worst of all–the “Morris” name.

Jim Nash said he’d try drawing up a formal contesting of Sam’s will. He even got Will Foster, the Baileystown coroner, involved. Will Foster swore he’d examine Sam’s body, spot Ally’s wrongdoing, and set the record straight. His examination came and passed, never producing anything. Two days after it, Gussie Parsons tried asking him about Sam.

Will told her, “Sam’s daddy’s up in heaven would be ashamed of him.”

He wouldn’t share anything else.

Three weeks later, Ally opened her flower shop back up. No one knew why she’d bother trying to sell flowers again, especially after the death of her only customer. On her first day back, she headed into town before sunrise. Ally paused in the middle of the road right in front of her shop, looking up above the door and up to her sign. As light barely started to shine out from the horizon, Ally noticed etchings.

Over the painted-on “HER’S,” someone had carved:

“HERALD OF DEATH”

Ally stood beneath the sign, stared up at it for a bit, as if she tried to take in each letter one by one. Teardrops swelled up in her eyes. She tilted her head back almost to balance the tears in her eyes. She held them there, never let them run down her face, never let the town see her cry. Then, she wiped her eyes, scoffed, and hurried on in for another day of sitting in a customer-less flower shop.

Townspeople kept walking in front of her shop that day, trying to catch a glimpse of her, maybe even get to watch her unceremoniously take down her own sign. Nothing happened. The sign stayed up. No one even saw her go home later that night.

The next morning, the carving had been traced over with the same black paint Ally used for the original sign. Now, above the little wooden shack of a flower shop, the sign read:

“HERALD OF DEATH: MRS. ALLY MORRIS”

The shop was empty. The ranch house too. Nothing more than a few cobwebs and dried up leaves were left to the Morris legacy. That, and on the door of the flower shop, Ally had tied a green carnation on the handle before skipping town.

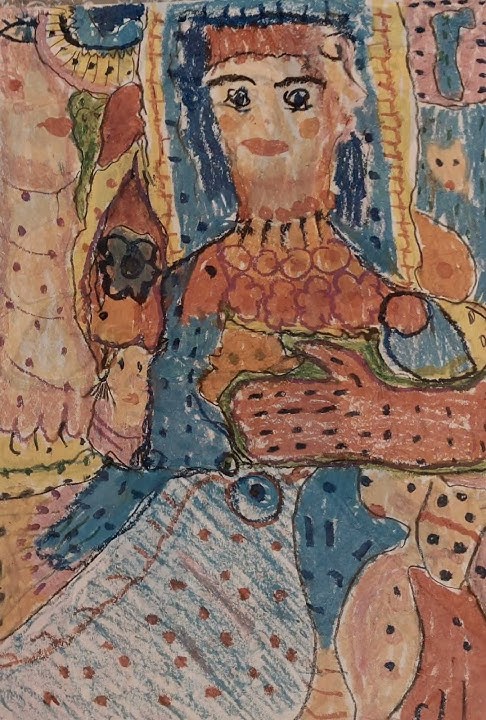

Untitled

by Güliz Mutlu

Kyle Lauderman is an author of prose writing from Cincinnati, Ohio. He is working towards completing his MFA in creative writing at Eastern Kentucky University. His latest short story, “Homeowners Oppression Association,” appeared in the Alchemy Literary Magazine. His self-published graphic novel, Boleyn Ballads, is available on Amazon.

Guliz Mutlu

https://youtube.com/@gulizmutlufineartportfolio

Birth Date, Place: 24/07/1978 Ankara, Turkey.

Current Location: Ankara, Turkiye.

1981. Golden Palette Competition Talent Award by Turkish Painter Nurullah Berk (1906-1982). She draws every day with colored pencils.

2008-2009 University Pompeu Fabra, Barcelona, Spain. Postdoctoral Degree on ‘Tenebrism Art’.

2008-2023 Ministry of Culture and Tourism, Museums Department, retired.

She is also North American Haiku writer to Modern Haiku, Frog Pond, Heron’s Nest in USA. The Mainichi Newspaper, Asahi Shimbun Newspaper in Japan.