by Elaine Ferrell

Gabrielle was sixteen to my thirteen. She openly smoked, drank on the sly, and was often in trouble with her parents. I worshiped her.

I admired Gabby’s lanky posture, for I was short and slouchy. I revered her long, straight hair, since my own was curly, tangled, and wild. Lamenting my boring brown eyes, I extolled Gabby’s large, blue ones along with her cheekbones: so sharp they could cut you. Her mouth was perfected by a dimple on each side and an easy, wide smile that sucked you in.

Our fathers were close friends, though gatherings with our parents were sometimes awkward, as I was her antithesis—bookish, afraid of getting in trouble, uninterested in experimenting with drugs, boys, or anything else. Regardless, I was delirious with joy at a chance for friendship with Gabby. While she was deep into adolescence, I was of an age in which I still engaged in a game of tag with childhood: sometimes chasing it and other times running from it.

On our yearly beach trip, these canyons of divergence in our personalities didn’t seem to matter. It was one reason I looked forward to that trip each summer. The beach possessed the power to balance: while there, your age and social standing disappeared. Building sandcastles was a team effort, with everyone working together to create a kingdom we could be proud of. Being in the ocean was full of possibilities: digging where the waves broke to determine how deep our holes could go before being consumed by water; swimming out as far as our arms would take; treading water and dunking our heads under the waves to cool off.

Each July, my parents rented a house in the Outer Banks of North Carolina for two weeks. While my family stayed the entire time, the house was full of nomads, with some people staying for one week on either side and some people straddling a week. My parents always figured out where people slept, even if that meant on a couch. As a result, our beach vacation was abuzz with activity, perpetually bursting with bodies. The house this year had a wraparound deck that looked down onto the ocean from one side and the road from the other. From the deck, there were steps that led directly to a walkway, which led to the beach.

As I packed for our trip, I daydreamed about hanging out with Gabby, imagining our conversations: I would show off my new swimsuit to her—a two-piece!—and we’d talk about the cool, new, summer hits. I spent the six-hour car ride down eagerly anticipating her arrival, thinking about what we would do together: tossing Frisbees; walking to the hot dog stand; riding the waves. I harnessed these images with a determination Icarus must have felt flying toward the sun.

As a house of primarily adults, we kids had nowhere to stake our claim. The adults claimed the open area that served as the dining and living rooms as their own, riddling it with various adult entertainments: cassettes of The Rolling Stones and Linda Ronstadt (yuck!), books brandishing authors for old people—Elmore Leonard and John Grisham—and activities like half-finished jigsaw puzzles and boring backgammon. The deck and kitchen were likewise peppered: smoldering cigarette butts; liters of vodka; lime wedges dripping juice onto the cutting board below. The house swelled with adult conversations lubricated by liquor.

In past years, Gabby and I had spent these sultry, summer days engaged in typical beach activities, playing games in the ocean: pretending we were mermaids who got washed out to shore; splashing each other in playful water fights; boogie boarding on top of the waves. We played games in the sand: digging up little sand crabs and plopping them in buckets; letting wet sand drip from our fingertips to design postmodern sandcastles; burying each other in giant holes.

At lunch, we sprinted to the house to wolf down sandwiches, then raced outside to do it all again.

***

On the first day of the second week, just after lunch, I was surrounded by hairy beer bellies and baritone voices, trying not to listen to Joni Mitchell. While reading a book on the porch, I heard my dad yelling toward the driveway. I looked down to see Gabby and her family—dad, Tom, and two brothers—huddled outside of their car. Any desires I had of befriending Gabby this year were quickly quelled: she had brought a friend with her! Right then, I vowed that this friend—this Kate, this thorn in my side—would not interfere with my Gabby fix.

Gabby and Kate unpacked their stuff from the car and carried it up to their shared bedroom across the hall from mine. I heard them giggling and whispering behind their closed door, then watched them walk down to the beach together. Did they just not see me or were they ignoring me? I decided on the former.

Dressed in string bikinis that showed off their supermodel abs, they each lit up a cigarette. I chased after them, my eyes daggers toward Kate’s neck.

“Hey, Gabby!” I called, but the wind caught my voice and they didn’t hear me. I ran toward the ocean, where Gabby and Kate were headed. They paused at the ocean’s edge, dipping their toes in and took long drags on their cigarettes, making shapes with their mouths in an attempt to make rings. Unsuccessful in this endeavor, they cackled, pointing at the distortions on each other’s faces.

I caught up to them, out of breath. “Hey, Gabby!”

She acknowledged me and introduced Kate. I waved hi, trying to do so excitedly, but not too excitedly.

They dropped their cigs into the sand, snubbing them out with their freshly-polished toes. Gabby and Kate careened into the ocean, their angular arms like wings. I followed, pining for the ocean’s equilibrium.

We laughed as the sea washed over us, readying ourselves for the swell of water. The three of us caught the same wave, riding it to the shore, then swam against the current to push ourselves back out. As we treaded water waiting for the next wave, Gabby and Kate gossiped about other girls, professed their love for certain boys, and argued about the latest fashions. I devoured their conversation, inhaling it greedily.

“Did you hear that Jenna made out with Steve in the east stairwell?”

“Oh my god, Dylan is soooo dreamy!”

“Ugh, I hate strappy sandals!”

I wanted to know how scandalous the Jenna and Steve situation was. What did Dylan look like? I didn’t like strappy sandals either!

I was further buoyed when I was able to hold my own in a conversation about Titanic, as all three of us discussed the dreaminess of Leonardo DiCaprio.

“Oh my god, his hair!”

“Oh my god, his eyes.”

“Oh my god, that smile!”

Gabby, Kate, and I were equals for those precious moments, with the same goal in mind: battling the capricious ocean by mastering its crests.

***

When I was nine or ten, we were at the mercy of a rainy beach week. Gabby had come down with her dad and brothers, but not her mom. This would have been the summer she was twelve or thirteen. Gabby was constantly fighting with her younger brother, and since it was raining all the time, everyone was huddled together in the beach house most days, making for some uncomfortable and cramped moments.

My mom suggested that Gabby and I go play in my room for some privacy, and handed us some paper and crayons. Gabby sneered—she was too old for crayons—but decided the reprieve was welcome. She suggested we draw our families and cut out the pieces. We would act out a play with our drawn-out family, she suggested. I drew my mother, father, little brother, and myself. I outlined my dad’s glasses and salt-and-pepper beard and my mom’s curly black hair. I exaggerated my own wild hair for dramatic effect and gave my brother freckles. He would look better with freckles. I glanced over at Gabby’s make-believe family— two parents who looked angry, and two little girls. She had not drawn her brothers. Is one little girl me? I wondered with a thrill.

Once our pieces had been cut out, I acted out an improvisational piece without much conflict. The kids argued over something mundane before the cartoon mother butted in, then the dad drawing made them all dinner and they were one happy family. When it was Gabby’s turn, she acted out a rather dramatic narrative with the parents fighting about something decidedly not mundane, though I couldn’t tell what it was. At the end of her sketch, the mother figure stormed out in a huff, then the two little girls confronted her. Gabby ended her play with these two girls stomping on the mother while laughing uproariously.

I wasn’t sure how to react. Did she want me to be upset? Angry? Or was she simply acting out a plot she had seen on TV and wanted me to recognize what it was? I couldn’t read the expression on her face, but she suddenly balled up her stick-figure family in tight fists and said, “Come on, let’s go get some ice cream.”

Her parents had divorced six months earlier.

***

But this year, at thirteen, I had a chance for a fresh start. Kate—the interloper, the barb—was just a minor inconvenience.

One evening, several of us went onto the deck after dinner, as usual. Gabby had snuck some rum from the kitchen and poured rum and Diet Cokes with lots of ice for all of us in red Solo cups. So far, no one was suspicious. I was thrilled she had included me in this salacious action. And while I liked the sweetness of the rum, I did not enjoy the sour aftertaste. I sipped it very slowly; though with every sip, it seemed to get sweeter. We played a card game, and I was elated for another dose of their dialogue. At some point, I went inside the house, and when I got back to the table, Gabby and Kate were gone.

Hawk-eyed, I tracked them to the stairs that led down to the beach. I shouted back to my mom, dad, or anyone who could hear me: “Going down to the beach, bye!” Without hearing a response, I bolted down the stairs and caught up with Gabby and Kate. I was unequivocally grateful for Gabby’s smoking habit, since they had both stopped to light up cigarettes, allowing me a chance to catch up.

They both waved to me, which I silently celebrated. We stood there for a few moments, allowing me to become intoxicated with Gabby’s smell: rum, smoke, saltwater. Gabby and Kate started walking south down the beach and I followed, drunk off their glee. They walked at a leisurely pace, but with their long, skinny legs, I had to speed-walk to keep up with them.

I was euphoric listening to them discuss anything—the weird mark on some other girl’s face, their horrible math teacher.

“Is it, like, a birthmark?”

“No, I think it’s a giant mole.”

“Ew!”

I scratched a freckle on my cheek.

“Ugh, I hope I don’t get stuck with stupid Mrs. Shit-ford again next year.”

I giggled. “Haha, shit-ford! That’s good.”

“Wish I could say I made that up,” Gabby responded.

I felt like I could fly.

I don’t know how much time passed as we continued to walk. It could have been twenty minutes. It could have been an hour.

Just in front of me, Gabby’s and Kate’s feet seemed now to connect to one large creature. The Alice in Wonderland caterpillar blowing rings of smoke from its double mouth. The smoke blurred in the air and reeked as it dissipated.

“Hey,” I asked, “Where are we going?”

“I dunno,” Gabby responded, “Just walking.”

“Oh. Well, I’m tired of walking. I’m going back home.”

My feet started hurting. I wanted water to suppress the acerbic taste of the rum, prevalent in my mouth again.

Gabby shrugged, and she and Kate continued walking while I turned back toward home, tired and achy. A little dizzy.

It was a starless night. Night on the beach is a different beast than night in the city: everything looks the same and there are no obvious markers to tell you where you are. Near the ocean, where we walked, there was no light. Beach houses emitted some light from several yards away, though it was not enough to really see where you were.

And I was now by myself, which made it worse. The ocean must have been at high tide, for I was walking fairly close to the houses, yet felt the water nipping at my toes. The ocean was as black as the night.

My legs were a burden. They dragged through the sand unevenly. They were all but useless on the minuscule shells and the water-logged shore.

But I pressed forward because I had to. I tried to take my mind off my worthless legs by looking for the house on my right. Is that it? Uh, does our house have a pointy roof?

My throat was dry.

I considered walking on the street side of the houses. But I didn’t have shoes on, and wouldn’t be able to see if I were about to step on sharp pebbles or broken glass. So I continued north, on the sand, toward the house.

I would get there eventually.

Why aren’t I home yet? Or wait, did I pass it? No longer able to smell, see, or hear Gabby, I began slouching. Shuffling. I was irritated. Anxious.

My legs wanted to give up. I drilled them to keep going: One two three, hut! One two three, hut! I was sweating despite the cool night.

I desperately wanted some water. I laughed to stop myself from crying. How did I get lost going in a straight line?

I walked slower and slower until I finally collapsed, facing the sea. The whooshing of the ocean mocked the sounds of my sniffling. I was tired. I was frustrated. I was scared. Where the hell is the house?

A man came toward me. He had been standing nearly parallel to where I sat down. I think he had been fishing.

Do my parents know I’m here? What time is it? When is Gabby coming back?

I couldn’t see him well in the dark, but could tell that he was tall and muscular. I dug my toes further into the cool sand and did not look at him.

“Are you okay?” the man asked, approaching me and kneeling.

His voice was buttery. Charming with an undercurrent of deference.

I sniffled and tried to compose myself. “I went for a long walk. And now I can’t find my house!” The last word punctuated by tears streaming down my cheeks.

He was sympathetic, but did not move closer. “It’s hard at night, isn’t it? Do you want me to walk with you until you find it?”

I didn’t answer. I wasn’t sure what his endgame was.

Then out of the corner of my eye, I noticed lights. I glanced north and saw two bobbing flashlights, which prompted me to stand up. Even with tears blurring my vision, I recognized one of the figures—my dad! I told the man what I saw and thanked him.

My dad became a beacon as the moon shined off his bald head, and I dashed toward the shadowy figures like a ship toward a lighthouse. My dad and Tom explained they were scouring the beach looking for Gabby, Kate, and me. “No one saw you leave!” he scolded.

I hugged my dad tightly, and he responded in kind. Then his relief transformed into a barrage of words: “Where the hell were you? Why didn’t you tell anyone you were going? Do you know what time it is? Where’s Gabby?”

His anger triggered my tears again. But after more hugs, explanations, and apologies, my dad led me back toward the house. Tom kept walking south to find Gabby and Kate.

As we walked, my dad ordered me to go to bed.

“I want to wait up for Gabby,” I responded.

“No. It’s late. You need to go to bed.”

I did not protest. I was just grateful to have found him, to not be alone on the beach at night.

Once back at the house, I went to bed like the obedient daughter I normally was. The next morning, I found Gabby and Kate sunning themselves on the beach. I did not bother them. Instead, I chose to bury my nose in a book on the deck.

0443E0B8

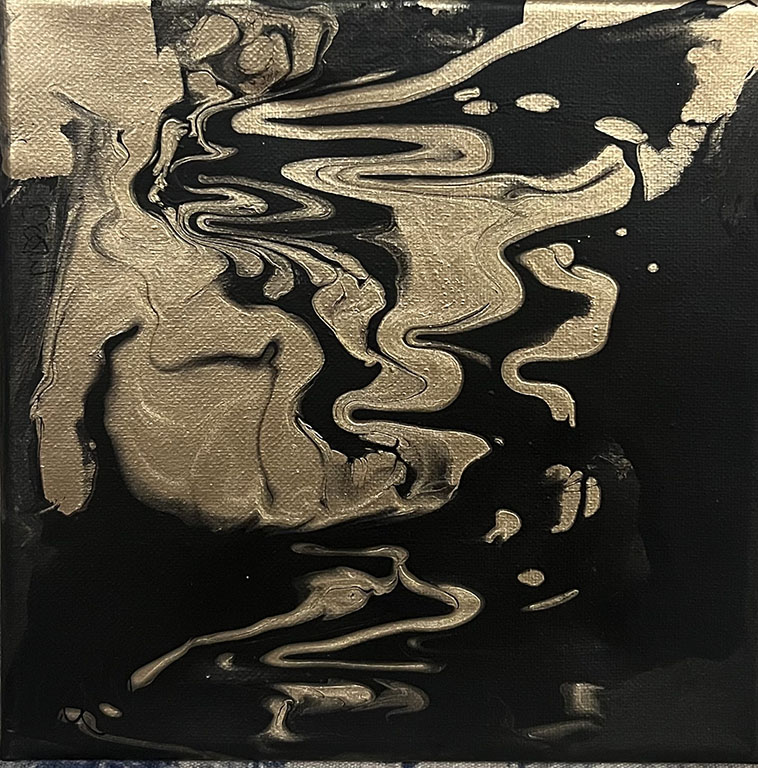

by Carolyn EJ Watson

Elaine Ferrell lives in Silver Spring, Maryland, where she works in marketing and communications. When not writing, Elaine enjoys baking and spending time outdoors. Elaine has been published in various publications, including ellipsis literature & art, Motherly, Small Leaf Press (UK), Soliloquies Anthology (Canada), and others.

Carolyn EJ Watson is an interdisciplinary artist who is drawn to the useless and unusual. She takes what she can find to tell a story using a mixture of unconventional materials. Through her art, Watson strives to advocate and educate, particularly focusing on concepts such as identity, trauma, abstraction, chaos, and conservation.