by Jacob Dimpsey

Lakshmi told me Manjeet’s parents sacrificed him to the gods. Cut his liver from his side and offered it dark and pulsing to a witch doctor. People are growing desperate, Lakshmi said, and some have turned to black magic. Monsoon season came and went with little more than a few drops of rain to stick the dust to the earth under our feet. Harvest from my father’s rice fields shrank again this year as it did last year. The roots could not grow deep enough into the parched soil. The leaves could not snatch enough sunlight from the grey sky. We used to sell our excess yield in the village market. But now we could hardly grow enough to feed ourselves. So we prayed to the gods for rain. And now Manjeet was dead.

During the planting season, I skipped school to help my father in the fields. Lately, I had been missing school to learn how to weave saris with the village women. Machines could make them cheaply, but we made them by hand, the way our ancestors made them for thousands of years, because they fetched a higher price at the Faizabad markets. Tourists who ventured this far into our country wanted to purchase a piece of our culture. Not just a piece of fabric.

Lakshmi was not pleased that I had neglected my studies. When she first arrived on holiday from the university in New Delhi, I could hear her speaking to my father after I had gone to bed.

Is this the life you want for your daughter?

My father was not as traditional as some of the other men in our country. It did not wound his pride to be questioned by a woman. My mother was traditional, however. I couldn’t see her, but I could imagine her stewing on a mat on the floor, hot tea cupped in her hands. She would admonish Lakshmi when my father was not around.

Suri will do as she pleases, just as you did, the low thrum of my father’s voice replied. But we are hungry.

Lakshmi’s voice, softer: I will try to send more money when I can.

My father was silent. The sweet smoke of his loosely rolled cigarette filled the house. After a while, Lakshmi left my parents and laid next to me on my thin pallet on the floor. She rested her soft fingertips on my forehead.

Suri, she whispered. Don’t you want to go to school?

I pictured the village school. Its brightly colored classrooms. My friends there. Playing football in the patch of dirt outside. Trading jokes and lunches. But I didn’t care for classes. I didn’t like sitting inside all day. I didn’t like learning English from volunteer white teachers who smile at us with blank, dull eyes. I only liked sustainability class. We learned water conservation, farming techniques, how to create our own energy, how to prepare for extreme weather. But I had learned many of those things from my father already. He could have even taught me English if I had asked him to. And everything else, I learned from Lakshmi.

I shrugged soundlessly in the dark.

Lakshmi shifted her weight so she could face me. The shadows on her face grew more pronounced.

Do you want to stay here forever?

She said this as if it should be obvious that I didn’t. She had said the same thing to Arun when he told her he was dedicating himself to Rama at the temple school in Ayodhya. She always strongly pushed me to follow in her footsteps, to go to university. She studied the climate and brought her research home with her to show me. She displayed graphs and sets of numbers, explaining how, if global carbon emissions are cut back by fifteen percent, the UN can reduce the rate of stratospheric sulfur dioxide dispersal by forty-five percent. Enough to bring back the monsoons. She traveled often for her research. Measuring the acidity of rain in different ecosystems. Meeting with biologists. Comparing the increased crop yields in places like the US and France to the decrease in India and sub-Saharan Africa. Attending conferences. She showed me pictures of faraway places on her phone and looked at me expectantly. You could go to these places too.

I’m part of the ecosystem here, I told her, using vocabulary I learned from her. Like pollinators and mango trees.

Lakshmi’s face softened.

So, you do listen to me when I read to you, she said, poking me in the ribs.

We both laughed, but a twinge of sadness caught in her throat. She would have yanked me up by the roots if she could.

I woke to Mother performing puja at the household shrine, kneeling before images of blue-skinned Vishnu. A bowl of incense smoldered among the fruit and flowers she had placed there. Fragrant smoke wafted through our small home. Lakshmi eyed her from where we were seated, eating our breakfast of chana masala. She had concerned herself less and less with the gods of our country. Instead, concerning herself with gods whose deeds are more readily apparent.

No one was prouder of Arun when he dedicated himself to Rama than Mother. He always preferred to study the Upanishads and the Ramayana than to work in the fields with my father. For a time, he worked as a brickmaker at the kiln down the road for paltry wages. Now I only see my brother when we go to the city for Diwali and Durga Puja.

I used to visit Arun at the kiln when we were younger. The kiln was a massive clay smokestack that rose higher than any building in the area, surrounded by a sprawling red landscape of workers gathering clay from the ground and packing it into wooden molds. I could barely distinguish the dusty skin of the workers from the dust of the earth. Lakshmi once told me about the companies and nations who are planning to colonize Mars. I asked her what the surface of Mars looks like, and she said to picture the kiln.

I would bring Arun lunch wrapped in a rag torn from an old sari. We would eat together under the shade of a stack of finished bricks.

The gods are angry with me, he said one day, taking a bite from a ball of rice like a fig.

I wiped my chin. Why?

His eyes were hard agate and his muscles tense. At only twelve, he looked much older than he was.

Because I am beginning to hate this land.

According to my mother, to hate the earth is to hate the gods. Lakshmi once told me she hates the gods but loves the earth. Sometimes her heresy scared me. Other times, I was emboldened by it.

After Durga Puja that year, Arun enrolled in the temple school. The next time I saw him, his edges had rounded. His shaggy hair shaved, his thin trousers and tank top replaced by orange robes. Already, he looked like a pujari. He knelt with me on the banks of the retreating Ghaghara. We lowered a tiny idol made of bound rice stalks into the river for our family. My father told me about the huge, ornate idols of Durga that my grandfather used to paint in exquisite colors for the festival. But such idols were illegal now because they would block up the shallow waterways. We offered prayers as our small idol was immersed and floated away. Arun whispered, You are rice, you are life, you are the life of the gods, you are our life, you are our internal life, you are long life, you give life.

When Lakshmi and I finished our breakfast, we took the clay water pot from its place near the stove and walked outside. My father was in the field, digging a new irrigation trench, trying to guide what little water he could find to the rice that needed it most. I waved to him and set the water pot on my head. The road was dark and cracked. A trail of wheel ruts and footprints were baked into the dirt from the last time the ground was soft enough to be imprinted upon. Dead patches of earth divided up the rice fields, serving as boundaries between one farmer’s land and another’s.

I walked this path for water every day. We used to have plumbing in our house, but as clean water became scarcer, access to it in the village shrank to a single well. We used to have electricity as well. But now it only came on once or twice a week.

It took a long time for my eyes to adjust to the morning light. When there were no clouds, and there often weren’t, the grey sky shone intensely. Lakshmi told me this was because even though the particles in the stratosphere reflected sunlight, they also dispersed it. That was why, on sunny days, the sky glinted with a metallic sheen that hurt your eyes. Why stars appeared blurry at night. And why we had sunsets that cast a fire from one end of the horizon to the other.

I remember when the roads would become so muddy this time of year, it was nearly impossible to walk to the village, Lakshmi said.

She was ten years older than me and remembered many things that I couldn’t. Blue skies and a lush green country with full harvests. Lakshmi had lost more than I had. She grieved in ways that I didn’t.

She used to tell me stories of the world she remembered at night as I fell asleep. Our school had a telescope, and we could see the rings of Saturn on clear nights. I learned how to find every planet. I thought they were all beautiful. Like marbles. When I think about the way things used to be, I feel like I’m on Mars, looking back at the Earth I once knew, as if through a telescope.

It wasn’t all good though, she said. It was hot. Very hot. Your skin was always sticky. You never felt clean. The heat killed people. Especially at the kiln. And the monsoons didn’t just bring rain. They brought floods and winds that would topple houses.

Once, she told me the story of how our father came to live where we were now. Before we were born, Father worked at a resort in the Maldives. That’s why his English is so good. He captained a yacht for tourists who wanted to explore other islands. His first love, he said, was those islands. He read about them growing up in Lucknow and as soon as he was able, he traveled hundreds of miles to work there. But the islands don’t exist anymore. When the ocean swallowed them, he moved back to Lucknow, where he met Mother. But he hated the smog and the traffic and the noise. So, once they saved up enough, they bought our little farm.

I asked my father about the Maldives. I wanted to be able to picture the islands in my mind where the ocean couldn’t snatch them away. But he shook his head and returned to what he was doing. Just as we imprinted on the land we walk on, the land imprinted itself on us. Even as it disappeared or changed beyond recognition, the impression it left hardened like mud.

Lakshmi gazed across the landscape. Her eyes were far away. She was probably trying to calculate the exact amount of rainfall we received this season. Comparing it to last year and the year before. Laying the dry land around us over the land she remembered in the form of charts and graphs. A man rumbled past on his motorbike. I steadied the water pot on my head.

In the village, there was a short line in front of the well spigot. We took our place and waited. Around us, the village bustled about. At the market at the end of the street, vendors sold vegetables from their gardens, clothing, and chickens. The school was empty because it was a Sunday. Someone was cooking vindaloo. The smell wafted over the dusty village and mingled with incense smoke from the Shiva shrine nearby.

Suddenly there was a frenzy of shouting and wailing from across the village, past the marketplace. A group of people rounded the corner, carrying a bundle of something. I tried to get a better look as they moved closer, but the crowd only grew larger.

Lakshmi whispered, Oh my god, and then the crowd shifted enough to reveal a small body in the arms of the villagers.

I dropped the water pot and moved closer to the group of people. Lakshmi tried to hold me back, but I pushed forward. The men carrying the body set it down, feet first, on a wooden bench. The body was wrapped in a long blanket. One of the men, a farmer who lived outside the village like us, unwrapped the body to show everyone. It was dirty and stiff and swollen in places. I froze when I recognized his face.

I used to watch the other children play football in the schoolyard in between classes while I wove saris with the women. Sometimes the women would let me play with them until they returned to their studies. I liked playing with Manjeet. He played football with an intensity that the other children didn’t, stamping the dry ground like he was trying to pound the life out of it. Sometimes he would give me a ride home on his bicycle.

The farmer gingerly lifted the hem of Manjeet’s shirt to reveal a deep gash below his ribs. His liver was removed, the farmer said. I found him near my field.

People began to murmur. Black magic. I squeezed my eyes shut and pressed my face into Lakshmi. She held my head and pulled me away from the crowd.

Lakshmi guided me back to the well. We stood by the Shiva shrine as the authorities arrived. They scattered the crowd and examined the body. Two officers broke away from the rest and asked members of the village where Manjeet’s family lived.

Lakshmi silently filled the water pot and heaved it onto her head. She beckoned me to follow her, and we set off back to our farm. Lakshmi used one hand to balance the pot and one hand to grasp my arm.

Why would someone do this? I asked.

I’m sorry, Suri, Lakshmi said, her voice cracking.

Her chin was held high, her head steady under the weight of the water.

I pictured a world with Manjeet riding his bicycle through the village and kicking a football against the school wall, catching bugs in the rice fields. I pictured Arun in his orange robes standing in the shallow Ghaghara. I could see them, but only from far away and through the haze of the stratosphere. I looked down and noticed I had begun to cry. My tears fell onto the dry road, creating tiny spots of mud. I wiped my eyes.

When we returned home, Lakshmi took the clay pot into the house and I ran into the fields. The soft, grassy leaves tickled my arms as they swayed in the wind. I wished my tears alone could water the whole land. That the monsoons wouldn’t need to return because my sadness was great enough to sustain all of India. I found my father sitting among the parched rice, face to the west, where fire ignited when the sun set. I sat beside him, but I said nothing. Without looking at me, he took my hand. His lips moved in a silent prayer to the distant gods, earless and holy.

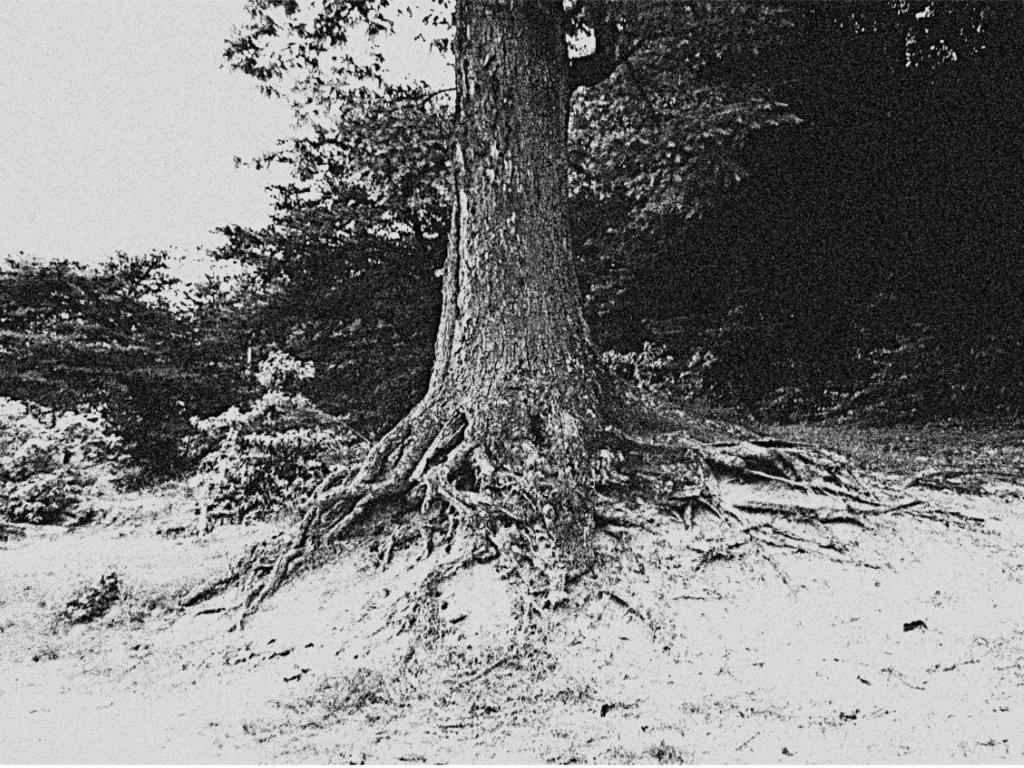

ROOTS

by David Summerfield

JACOB DIMPSEY is a writer living in Central Pennsylvania. His work has previously appeared in The Blood Pudding and The SFWP Quarterly, among others.

DAVID SUMMERFIELD, editor, columnist, and contributor to various publications within his home state of West Virginia, has published numerous works of fiction, nonfiction, poetry, and photo art in a variety of literary arts magazines/journals/and reviews.